|

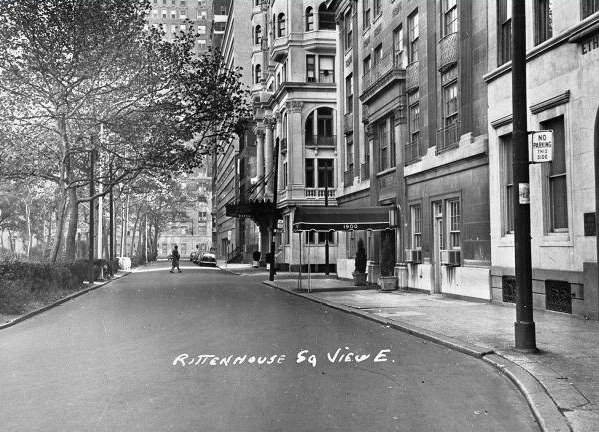

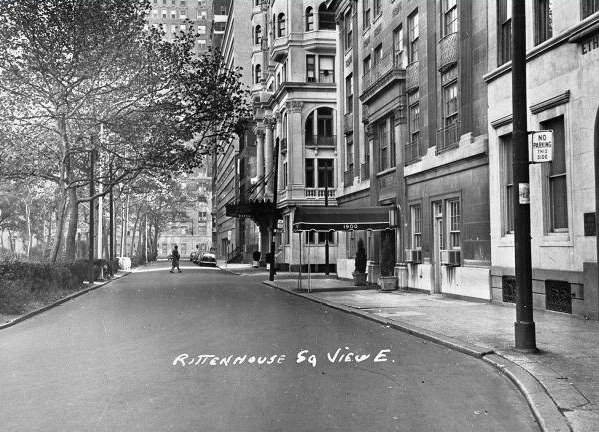

| 18th and Locust Sts, 1959 |

By Sam Allingham

Mrs. Kingsley was sitting in the Southwestern part of the square where there wasn't much sun. It was the relative middle of July. Sitting in the sun, the heat was overpowering. When she was younger she had enjoyed the heat but her outlook was changing. People were bringing brown bags into the park and sitting by the fountain. The trees were waving. Everything was more or less normal.

Her husband was upstairs in the Addison talking to some men about the Cuban situation, the uprising. She understood that these men didn't like to call it an uprising. They preferred to call it a situation. In the end, the words mattered less than the reality, which was plain. Castro had Havana. Priorities would have to re-drawn, and so her husband was upstairs at the Addison re-drawing some priorities.

They were staying a few blocks off the square in the Dover. Edward - her husband - wanted to stay in the Rittenhouse, but they were full up. He made a grand show of being offended, because he knew she wanted to be near the square. He didn't care, of course. He would be in the Addison most of the day anyway, and wouldn't care if it rained or what the view was outside their window.

He hadn't been peering out of their windows in the Dover much. That morning he was fussing with his cuffs when a call came up from the desk. It was Carol, calling from New York. Carol just wanted to let her know that everything was fine with Willie and Charles, that the boys were going down to the Met with Phyllis. Mrs. Kingsley could imagine the boys, Willie's skin already tanned from the vacation, falling out of a taxi in their khaki shorts, all knees and elbows. Carol would make sure their hair was well parted. She was turning strict with them. Lately Willie was trying to resemble his father, standing tall in awkward imitation, paying attention to his posture. It was harder to whittle this away and show his loving, boyish qualities.

- And also, I thought you might like to know, it was in the papers here. That singer, the one we used to see over at the Carousel. She died.

Mrs. Kingsley touched the bunched length of the curtain.

- I think I remember. She had that lazy voice, we used to call it lazy.

- That's right! We used to say it when she sang "Up the Lazy River." That was what it was like, her voice.

- So she's died? That's terrible.

- Yes, it was in all the papers. You haven't heard.

- No.

She looked once more out the window, up at the sky. It looked like it was clear all the way to the horizon.

-And they she was born where you are, in Philadelphia. Lived there for a short while.

- Is that so?

Mrs. Kingsley looked down at the store across the way where they had papers in a box, the local papers. She hadn't even had breakfast yet. Maybe she would go down and have some tea and read the news.

The front page headlines were full of the usual substance. There was a steel strike going on. One concerned article on Cuba by some expert about how it was poised "like a dagger at the country's heart." Of course, everyone was talking about communists. Local stuff too, naturally. Philadelphia was still talking about the debut of the flag with the 49th star, some faraway frontier land. Local politics with which she was unfamiliar were discussed a little. She looked but she didn't buy. She was only in town for that day and night.

Instead she walked into the Square. It was an eggshell blue day. The sky could have been painted. The lunch crowd was present in full force, going through their motions. A man was selling sandwiches out of a little cart. She would have bought one, just to feel part of the scene, but her stomach felt vaguely uncomfortable, as if some remnant was lingering in it.

What was the name of the singer? She couldn't remember. She remembered her, that she would sometimes wear a red bow on the front of her dress as if she were a present for the audience. She was lazy in those uptempo numbers, slurring a little behind the band. What a thing, to just drop back like that and not care. She would flash the boys behind her a smile, teasing. And on the slow songs she was mournful, there was a sadness to her. Edward didn't like her. No maturity, he said. No range. Something childish and silly about her. There were rumors about drug use.

She was there at the Carousel for a month's residency. That was probably in 40, maybe early 41. Before the war. They came in many nights. Edward was working on some contract with the owner. He was starting into the nightclub business then. He said you might as well work where you enjoy yourself. At the time it seemed a neat and comfortable proposition. Sometimes she and Carol sat at one of the tables by themselves, to avoid the work talk, to listen instead.

- I think she has a thing with the trumpeter.

Carol would lean in. That was Carol's thing, this analysis of people. Carol did it all the time in those days. Sometimes it made her wince, because it was presumptuous. But of course most of the time Carol ended up being right. She was perceptive, then and now.

- Do you think? He's awfully dark.

- God, Elizabeth, you're so conservative. Sometimes it's astonishing. What does that have to do with it?

She blushed. It was just something that had occurred to her. It wasn't anything she could accurately justify. There it was.

- I suppose he is handsome, that's true. But he slouches a little.

- Maybe he's smoked tea.

That made both of them laugh, until they had to get themselves together. Their men were looking over at them and looking confused, perhaps hurt. Probably thought they were the object of the laughter. She was pretty sure Carol had never smoked tea. It was just something they had heard about, from certain people. It had been at certain parties, people spoke about it.

She always had, as a rule, three martinis up with olives. Edward had a similar rule with scotch. At the end of the night the singer - what was her name? - always played more ballads and blues, "Fine and Mellow" was one. Even Edward liked that. He got tired of talking business. He came over and took her hand in the white glove and gave it a pulse. There was the darkness of the club and the warm light of the candles on the tables and the lamps hanging on all sides of the stage for the musicians. The chime of ice on glass and the clicking of saxophone keys, beneath the music.

She sat in the park and watched the people begin to return to their jobs. It was hard to believe, in the presence of the moment, that she herself had no job to go to. In those days, the Carousel days, she had worked as a typist in Midtown. There were those sorts of jobs in Philadelphia, as well as New York. She had the funny idea that if she walked off to one of those jobs right now, off of the Square, she could do it. She could take off her thin coat and drape it across a straight backed chair. She would flex her fingers and sit down in front of the typewriter and begin as if she were continuing a job she had left off yesterday. Then, at the end of the day, she could rise and go to see some nightclub singer.

Then Edward appeared. She thought it was him, though he was far away. He was striding through another part of the square like a man with business, which of course he was. He had his hat off and a newspaper tucked under his arm. He would be hot in that dark gray suit but he insisted on darker colors because he thought - she knew - that they were more impressive. He would be paying for that now.

Everyone else seemed to have gone. A colored nanny was pushing a baby stroller across the under-populated park. She was talking to herself about the weather. Mrs. Kingsley felt strange, as if she had been speaking to herself as well. Pigeons clustered around the careless remains of someone's lunch.

She could have called out to him. Maybe he would have found it funny that they would discover each other in this unfamiliar park, like different people with other, separate lives. But she didn't call out. She let him go on towards some restaurant where important people were waiting for his news. He didn't like to be harried by odd circumstance. And who knows, she might have been mistaken. The lunch hour was full of men in dark suits pressing on into the world.

She went on sitting, longer than she even wanted to. She felt strangely abandoned, although she couldn't say why, or by whom. The day went on shining for no one's benefit except her own. It seemed like a lonely position to be in, to be the sole audience for the beauty of the world. Even the nanny was gone, and the baby for which she was responsible.

What had happened to that singer? She lost her cabaret card, Mrs. Kingsley had heard about that. There was the war, and there were always rumors about drugs. And she made a song, a serious song that some people approved of and for which some people had less fondness. Someone wrote it for her. People said this writer was a Communist, a lot of people had that suspicion about him. And now, apparently, she was dead.

It was still hot when she got up. Her vision was cloudy for a moment and she felt faint. She pushed through it, across the park. She moved out of the shadows into the sunlight where a few people were still crossing from the Castle Arms into a booksellers and a news agent. Her husband was by the Castle Arms with a few men in lighter summer suits.

- Elizabeth. Gentlemen, this is my wife.

She said hello. She felt off-base, and she thought they could sense it. Maybe there was something wrong with her, or her clothes. Maybe there was something missing. She struggled with the greetings as she tried to understand what was wrong. Instead, the name came to her tongue, finally, like a stutter giving way.

- Holiday. The singer, she died.

The men leaned in a little and put their hands in their pockets. They were all a little older than her husband, but somehow sunnier, as if they had license to be. One of them smiled and stroked his chin, looking newly shaved. They asked questions, one after another.

- Who's she? What singer?

- I don't believe I know her.

- I may know the name. I think I know it. Who was it again?

They were trying to pretend it wasn't strange. Edward looked off. He was making an effort, too. Then he spoke, quietly, as if about a player in some other city's baseball team who had suffered an injury.

- The negro cabaret singer. Rough voice, a little loose. Not mature.

- Yes, I remember. I think.

- Not well remembered. A big thing for a bit, a certain kind of singer. Solidly middle caliber.

They said a few more things about her that were all a little vague. It was hard to tell whether or not they had heard her from the things they said. Eventually the men all nodded and excused themselves. That was the end of the conversation.

The two of them walked back across the Square, towards the shaded section. She asked him what they were talking about and he told her they talked about business. She asked him what kind of business it was but he didn't respond. He kept running his tongue across his teeth in the left side of his mouth as if there was some food trapped there.

- Do I embarrass you?

- No.

He rubbed his nose and looked away from her, because he was lying, at a young couple who were sitting in the sun outside of a café. They were waiting for the check to come, silently, and kneading each other's legs under the table, where they thought no one could see. Mrs. Kingsley looked at them and wondered where they were going. Her husband was still talking, about how it was a hairy time and it was a shame of course that Batista was out because he had been excellent on business and his mind wasn't on anything else. There might have been an apology, couched and distant. She craned her neck to watch the couple a little more. It was the first time all day that she had seen this obvious happiness. Eventually they got away from her and disappeared in the flow of buildings. She found herself missing them. They were like nobody she knew anymore.

Back to main page.